How well do you know yourself? If pushed to the brink of your sanity, would you fall over or fall back? Would reason and decency prevail, or would it be no holds barred war with whatever you’re up against? Would you be guided by facts and proof or allow instincts and intuition to rule the day?

Jake Gyllenhaal and Hugh Jackman in "Prisoners" (2013)

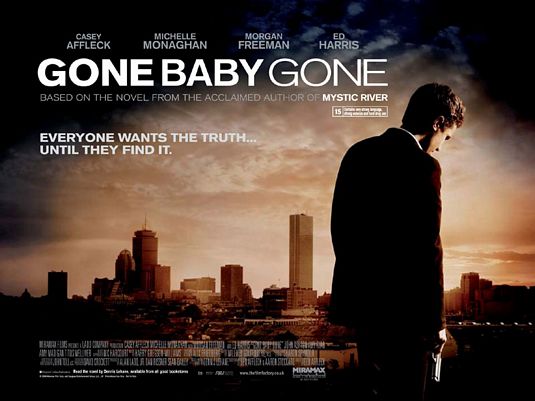

We all have a sense of what we would do in a given situation, but obviously we can never know until the situation is upon us. We never know what extremes we are capable of. It’s a theme that has come up in many films; characters are regularly faced with moral dilemmas big and small. But the matter has rarely been depicted so boldly as when characters are trying to deal with the loss of a family member, particularly the loss of a child. I recently saw last year’s “Prisoners,” starring Hugh Jackman and Jake Gyllenhaal, a movie that forced the audience to make judgment calls about what’s right and what’s wrong when innocent lives are at stake. It reminded me of another film from several years ago that forced the audience to ask similar questions – Ben Affleck’s directorial debut “Gone Baby Gone” (2007).

I guess the distinction I make between these films and other movies dealing with similar subject matter is that the men and women who are driven to desperation in these two films seem very much like everyday people as opposed to super cops or highly trained operatives like the men in “Die Hard” or “Taken.”

In “Prisoners,” directed by Denis Villeneuve, two working-class families are neighbors and friends. When their small daughters are abducted, one of the fathers (Jackman) is outraged when the police have to release the prime suspect (Paul Dano in what has become an all-too-familiar characterization for him). The young suspect does not appear to have the mental capacity to have committed the crime; yet when Jackman confronts him in the parking lot outside of the police station, he seems to admit he did it by saying loud enough for only Jackman to hear, “They cried when I left them.”

That’s all it takes to convince Jackman of Dano’s guilt, so he decides to abduct Dano and torture him until he breaks. And Jackman doesn’t hesitate to enlist the help of his comrade-in-grief whose daughter is also missing, Terrence Howard. But Howard, while equally desperate to save his daughter, is not as eager to operate outside the law or his conscience to do it. Keep in mind, neither of them knows whether Dano did it. Dano has been declared mentally challenged and was given an alibi by his mother (Is she protecting him?), so it’s possible that his whispered words to Jackman in the parking lot were meaningless. So as you watch you have to come to terms with what you believe, and whether belief in Dano’s guilt or innocence should matter. The ending makes those questions even more profound.

“Gone Baby Gone,” stars Casey Affleck and Bridget Monaghan as a married detective team who take on a missing child case that is a bit out of their league. But they are persuaded by the missing girl’s mother, who they know from their Boston neighborhood, and the gravity of the circumstances to investigate. Affleck is so moved by the mother’s anguished appeals for help (played wonderfully by the Oscar-nominated Amy Ryan) that he goes so far as to promise that he will find the girl.

The movie takes you through a lot of twists and turns as the detectives try to work with the cops – led by Morgan Freeman as the chief and Ed Harris as the lead inspector on the case – to get to the bottom of the crime. As they uncover more about the circumstances behind the abduction, they become more and more aware of how Ryan may not be the best person to be raising a daughter. The audience also becomes more and more aware of how the people who fight crime often feel compelled to bend the rules and alter moral compasses to achieve justice. For Affleck, the question becomes if they are able to save the child, would it be right to turn her over to an unfit parent? < SPOILER ALERT > Of course, that’s the very decision it comes down to – made poignant because the child is in a much better environment than she would be with her mother. Affleck has to make a choice that will determine the direction of the child’s life as well as his own because his wife is prepared to leave or stay based on his decision. We know he is capable of crossing moral boundaries because he does so earlier in the film in retaliation for a child he was unable to save. But you could see how torn up he was about it (and how comfortable his wife was with it). So what will he do now to protect a girl he can “save”? He is capable of going to extremes, but is he also capable of reeling himself in? Again, you’re forced to wonder about what is right and what is wrong and how the lines can easily blur.

Both movies are well-made, gripping dramas. The characterizations are much stronger in “Gone Baby Gone.” Ryan was powerful as the unfit but frantic mother, but I also really liked Affleck's performance. He was so believably tough to be such a lightweight. I guess it goes with having to know how to carry yourself even if you're a small guy. The script was adapted from the Dennis Lehane book of the same name; he's an author who frequently deals with such themes - as in "Mystic River." “Prisoners” certainly packs a punch as well, especially the ending, with solid performances from the entire cast. When you want to ponder some tough questions about what it means to do the right thing, these are two movies that will definitely get you going.